Why should Christians care about Artificial Intelligence?

Next in our Why Should Christians Care… series, Simon Cross writes about artificial intelligence. Dr Cross is the Research, Engagement & Parliamentary Assistant to the Bishop of Oxford.

In June of 2019 the UK Government published Regulation for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, its White Paper on technology and artificial intelligence (AI). Why refer to industrial revolution? There are those who suggest AI’s advent is more significant than the invention of the steam engine, that it is a technological breakthrough as momentous as electrification. Some see in this new industrial revolution the possibility for a technology driven nirvana with robots finally able to undertake all work thereby allowing us to repose. Yet others fear disaster as we naively forge the key that will open a Pandora’s box. Are such heightened hopes or fears really justified? Why should Christians care about AI?

What is AI

AI refers to computers or robots that perform tasks normally associated with intelligent beings, such as reasoning, identifying meaning, understanding language, generalizing, and learning from past experience. (Very) broadly speaking, this is accomplished by algorithms; clear-cut instructions that process data in a prescribed sequence to achieve a certain goal and provide a particular kind of solution. The most common type of AI involves Machine Learning; a set of methods for programming or training computers to automatically detect patterns in data, which are often beyond the capacity of human identification, and then to use those patterns to predict unknown (future) data.

Google data centre in Dublin.

Why, then, should Christians care about AI?

Christians should care about AI because it raises important issues that society has yet to decide about. Much of the popular literature on AI settles around three perspectives on these issues.

1. AI will always be inferior – there are aspects of human-being that digital and information technology can never replace (soul, creativity, love…)

Those who hold to option 1 perceive a richness, depth, and wholeness to human being that resists a false tendency rooted in Enlightenment philosophy, as they see it, reductively to equate mind with brain and body with machine. Others may dismiss this high view of human capacities as old-fashioned and ‘unscientific’ insisting it ignores the sweeping implications of evolutionary theory. But some questions transcend science. Profound anthropological, philosophical and theological questions hinge on the meaning of the imago Dei, and it is clearly a matter of importance for Christians to contemplate the nature of not only mind and body but also the meaning of soul. How, for example, should Christians interpret the language of creation in Genesis and the divine act(s) of forming and ‘breathing’ in life (Gen 2:7)? Similarly, there is a rich literature in philosophy of mind concerning mental ‘zombies’ that can interact with the world in ways that might appear to reflect real dispositions yet possess no actual (internal) mental life. The thorny question then arises whether, how, and at what point AI might ever transition from simulated but ultimately zombie-like behaviours to genuine personhood?[1]

Automation in an Amazon warehouse.

2. AI will supersede humanity – doing everything that we can do but quicker and ‘better’, either making our lives easy or destroying us in the process.

AI is solving computational tasks previously far beyond the reach of human capabilities. It is, among other things, increasing disease diagnosis rates, and educational attainment, and boosting transport efficiency. Industrial robots are increasingly replacing human workers in mundane and hazardous occupational roles. Yet in many respects this onward march of progress is nothing new.

Thinkers from Karl Marx to Adam Smith imagined that machines played a key role in “de-skilling” human labour, For Marx, automation dehumanized workers. For Smith, quickening the pace and expanding the reach of machines left a clearer picture of what was divinely unique about humans. Both men, products of their time, assumed that automation’s intrinsic capacity to conquer all routine work was inevitable.

(Ghost Work, p. 58)

The optimists anticipate an AI driven age of ease. But some people fear AI’s potential capacity to conquer more than just routine work. They worry that we may imminently, albeit accidentally, release an uncontainable genie from the bottle. This group includes such notable figures as Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking who have both argued that AI poses a fundamental risk to our existence as a species. The Oxford philosopher Nick Bostrom posits a potential threat from even the most apparently benign AI accidentally destroying humanity simply by virtue of our programming it with inadequately precise high-level goals. His example is a robot tasked with making paper clips as efficiently as possible that eventually starts turning human beings into raw material for so general and unguarded a primary purpose. This more dystopian view of AI suggests a different theological challenge for Christians, namely how to discern the limits of human (co)creation with God and the meaning of the apocalyptic scriptures.

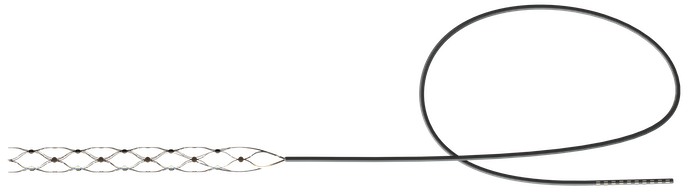

Stentrode, an implant—still in development—designed to allow people to control prosthetics by thought.

3. AI and humanity will synthesise creating a new and better kind of being: ‘transhumanism’.

Interpretation 3 is exemplified in the thinking of Freeman Dyson, Ray Kurzweil, and others who see a harmonious integration of technology and biology allowing our species to leave behind the limitations of finite embodiment, uploading our (digital) selves as information that can traverse and colonise the stars, living forever in a hypothetical virtual ‘cloud’.[2] Some technological utopianists see an affinity with the Catholic theologian Pierre de Teilhard Chardin’s Omega point and the merging of creation and God in the noosphere.[3] If this is correct, the Christian engagement with AI includes discerning the meaning of those scriptures that relate to divine purpose and to theosis: union with God. Yet technological transhumanism also raises theological questions about the significance of embodiment.

So which interpretation is correct?

Before adjudicating these options, it will help to consider the role of language in relation to both artifice and intelligence. It is a basic tenet of Christian doctrine, perhaps most clearly articulated by Thomas Aquinas, that our descriptions of God are analogical not univocal. Analogy confers an ‘is like’ pole from the original meaning of a word to its new meaning so that “God is love”, means God is like human love in true, meaningful and important ways. Yet the love that is God is also qualitatively different from, and therefore ‘is not like’, human love as well. The risk in using anthropomorphic language univocally when talking about God is that we reduce and diminish the tenor, making it identical to the vehicle. The imago Dei in us is not so easily resolved.

But in the context of AI, anthropomorphic language presents that same risk in its mirror image, potentially conferring more explanatory power on such words than is warranted. When developers refer univocally to an AI programme ‘understanding’ or ‘deciding’ or ‘learning’, they risk conferring too much significance on the term. For example, one of AI’s central conceptual terms is ‘neural network’ but this is an analogical reference to the biological brain and even the most sophisticated artificial neural networks in use today possess far fewer connections than, say, a Bumblebee’s brain. The term ‘neural network’ may be instrumentally useful but also philosophically reductive. Similarly, algorithms ‘decide’ by implementing mathematised rules of probabilistic inference, but, given the unresolved mysteries around consciousness and free will, this may or may not be akin to our own deciding in some approximate sense. Moreover, the pressure to monetise products and to generate financial returns on investment encourages, rather than inhibits, the tendency to univocally anthropomorphise AI because the claim that a technology can do something ‘smarter’ and ‘better’ as well as faster than an ordinary human is a powerful selling strategy.

With this caveat in mind, these positions are better viewed as a spectrum of possibility than fixed options for deciding on the importance of AI. But for evaluating their strengths and weaknesses as a whole the comparison with electricity is, in my view, helpful for locating concerns at the right range of significance. Technologising electricity has allowed tremendous changes in the way human society functions and has contributed to our collective flourishing in many and varied ways. Yet electrification also permits people to build devices for execution, while poorly designed or badly maintained distribution networks and devices can be accidentally or carelessly destructive. But electrification is no intrinsic threat to human identity. Neither, it seems to me, need Christians see the current (or presently foreseeable) capabilities of AI as anything more than a new set of tools. AI is not and – for the foreseeable future cannot be - more ‘human’ than its creators. This is not to deny, however, that the potential risks of misapplying AI are real and significant, even now.

If we combine these two insights: that of a continuum for help or harm, together with the risk of misattribution – and over-exaggeration - of AI’s capacities through naively univocal anthropomorphism, then a fourth concern arises. One that scholars are only now coming to recognise but that Christians, along with all of society, should pay close attention to.

4. AI will allow a powerful minority to manipulate and control the majority, thereby reducing everyone’s humanity.

Christians rightly care about the common good, but a number of recent books have begun to evaluate the social impact of Silicon Valley’s ‘Move fast and break things’ mantra and the acquisitive business models of technology-oriented companies like Uber, Facebook and Amazon. Again, two fundamental concerns emerge. First, a threat to our wellbeing through the loss of autonomy. Secondly, a threat to our welfare through the undermining of the social contract.

The Threat to our autonomy

The threat to our autonomy is most clearly articulated in Shoshana Zuboff’s account of Surveillance Capitalism, by which the cookies and tracking technologies that are now ubiquitously deposited on our devices harvest extensive and intimate data about us as ‘behavioural surplus’ to be used for commercial exploitation under the guise of personalised and bespoke service. This is more than a single technology like facial recognition or a single issue, like fake news. Nor is it only about discovering that harmful social biases are often locked into the algorithms we create and the data that is used to train them, real though these online and algorithmic harms certainly are. Rather, there are troubling questions around the meaning of ‘freedom’ itself when Facebook is able to conduct live experiments on user behaviour and when every aspect of our lives; from internet search results; to entertainment recommender systems; to what we come to believe counts as a reputable news source, is observed and intentionally influenced by opaque ‘black box’ proprietary algorithms. Tools created to achieve outcomes defined by, and in the interests of, vested business or political power. In China this extensive use of surveillance and erosion of individual autonomy now takes the form of Social Credit systems in which every citizen is rewarded, or punished, for specific activities like driving well or missing a rental payment.

The threat to Society

AI already affects the way we shop, watch television and socialise, all of which only add to the myriad of ways that AI is also changing work. Technology itself is, of course, inherently neither good nor bad, but the business models of Silicon Valley intentionally strip away many of the benefits and dignities of conventional employment and the current social contract, including holiday, sickness and pension benefits. Under the guise of convenience, flexibility and choice, these losses are portrayed as the unavoidable price for being your own boss in the so-called ‘gig economy’. But what else disappears if and when meaningful and properly remunerated work vanishes? Social investigators are now beginning to label certain working practices ‘neo-feudalism’ and some gig workers are now organising, lobbying and striking for better terms and conditions.[4] The Christian duty of care for neighbour and concern for those who are poor and marginalised means that we cannot absolve ourselves of the consequences for society as a whole, of business models that disrupt by lowering price and ‘friction’ in part through precarious and exploitative employment practices.[5]

Why Christians should care about AI

The imago Dei, while a powerful motif in Christian doctrine and Christian anthropology is an enduring mystery. Its paradox is, if anything, sharpened by the arguments of philosophers like Maurice Merleau-Ponty and the psychologist Ian McGilchrist, about the centrality of embodiment; a facet of being human unacknowledged or ignored by singularist theorisers like Ray Kurzweil. For all of science’s advances over the centuries, the distinction between life and non-life and the nature of consciousness remain as mysteriously intertwined as ever, and the recurring use ‘body’ by Paul in 1 Corinthians 15:35-58 suggests that we will forever be more than just ‘pure information’. The mystery of the imago Dei comprises, therefore, two inscrutabilities: divine being and human being. Furthermore, however we choose to read the text of Genesis 1-3, the imago is clearly mirrored in the categories of freedom, responsibility and relationship. For this reason, I suggest that Christians should be more concerned by the deployment of AI utilising so-called ‘dark patterns’ that psychologically manipulate technology users, and by the prospect of replacing human care-givers with robotic simulacra, than any vision of imminently traversing the stars, or death by paper-clip machine.

So, why should Christians care about AI? Because, simply put, its rewards and risks need to be balanced. AI is already bringing real and substantial benefits to a range of human activities from social connection to disaster mitigation. But the risks are also real, and the biggest risk AI poses may not be the imminent invention of autonomous Terminator type robots but rather the wholesale loss of human autonomy; and the widespread forfeiture of human dignity. While history will judge the particulars, there are few if any areas of our lives that will remain unaffected by this technology and the industrial revolution it is inaugurating. There is much, therefore, for Christians to care about AI.

Notes

1.It should be stressed, however, that the capacity even to simulate much that comprises human behaviour and abilities – so called artificial general intelligence (AGI) - remains highly speculative and far beyond either present abilities or the foreseeable technological horizon.

2. When evaluating the broader connections between science, technology and teleology Mary Midgley’s Science as Salvation (London: Routledge, 1992) remains a perceptive and helpful resource.

3. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, The Ascent of Man, (London: William Collins, 1959).

4. Alex Rosenblat’s Uberland (2018) examines these issues in the context of a single company, while Mary Gray and Siddharth Suri’s Ghost Work (2019) provides a fascinating and revealing exploration of the meagre terms and conditions faced by a vast labour force covering automation’s ‘last mile’, completing tasks that remain – often without the end user ever realising – beyond the capabilities of unsupervised technology.

Further reading

Mary L Gray and Siddharth Suri. Ghost Work: How to Stop Silicon Valley Building a New Global Underclass, (New York: Haughton Mifflin Harcourt, 2019).

Mary Midgley. Science as Salvation (London: Routledge, 1992).

Nick Polson and James Scott. AIQ: How Artificial Intelligence Works and How we Can Harness its Power for a Better World. (London: Bantam Press, 2018).

Shoshana Zuboff. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power (London: Profile Books, 2019).