What is a Christian vocation (and how to discern it)?

With Petertide ordinations around the corner, the School of Theology will be publishing essays on vocation, discernment, and ordination over the next weeks. First up, Fr Jonathan Jong writes on what a Christian vocation is, thinking especially about lay vocations. This essay began as a talk given at St Alphege's, Solihull.

The irony of a priest writing on lay or secular vocations is not lost on me. Even more ironic is the fact that I shall be doing so primarily through the lens of ordained ministry, which—for many, though hopefully not for all—will disqualify this offering altogether. In any case, my purpose is to consider how our theology of vocations to ordained ministry can inform our—lamentably much less developed—theology of vocations to other forms of work.

+++

There is a mistake commonly made in these heady days of late capitalism, which is to think of the word “vocation” as a near synonym for the word “occupation” or “profession”. And, to be sure, we are, all of us, called to be the best accountants and teachers and stay-at-home-dads and rock stars and hospice nurses that we can be, where “best” is relative, not to industrial standards, but to expressions of authentic Christian life. In that sense, the pairing together of vocation and occupation or profession is perfectly innocuous, even sensible. But there is really no reason to think that the primary locus of your vocation—that life to which you are called—should be the thing for which you are paid a salary.

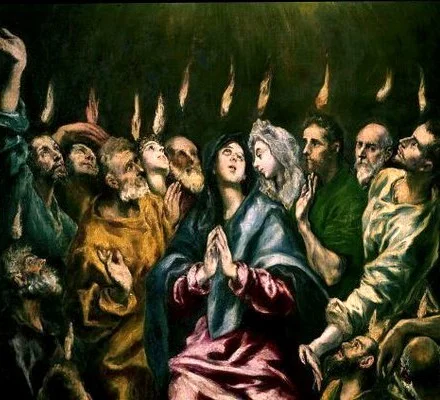

St Joseph the Worker, Monastery Icons.

Take the difference between stipendiary and nonstipendiary clergy, for example. As a nonstipendiary cleric, I am—I hope we all agree—no less called to the priesthood than my colleagues who are paid by the Church in some way. Speaking of payment, there is a bit of semantic pedantry that I think is theologically significant, and I wish informed our actual practice more. Technically, a stipendiary priest isn’t paid for services rendered. She doesn’t get a salary; rather, she is given a stipend to free her up from other work, so that she is able to serve her parish. Her priestly work is not her job, in the familiar sense. She is, in that sense, unemployed: she doesn’t do anything for a living. If this seems odd, it is only because the Church has bought into capitalism, hook, line, and sinker. I don’t get a stipend. And part of what that means is that, at least in my circumstances, I am not as free to do what you might categorise as “church work”. Annoyingly, I have to do other things like write papers and speak at conferences and supervise graduate students. Now, unlike a lot of 9-to-5 jobs, my professional career does afford me the flexibility to do things like celebrate mass and write sermons and visit the sick and attend PCC meetings. Lucky me.

The distinction between a salary and a stipend is important not least because no one should be a priest for the money; if any one of us discovered that we wouldn’t do the essential services of a priest for free if our circumstances permitted, we should probably never have been ordained. By “essential services of a priest”, I mean the sorts of things that appear in the ordinal: preaching, baptising, presiding at the eucharist, caring for the sick and the dying, and so forth. Of course, priestly work is not the only kind of work that people seriously consider doing for free. Lots of people volunteer for Oxfam or the night shelter. Lots of artists and writers and musicians would do what they do for free. Many teachers, who put up with funding cuts year on year, keep being teachers despite being able to make better money elsewhere, and then continue volunteering without pay after they retire.

This is one good place to start thinking about vocations, then: what work would you do for free if you could? It has to be work, of course. There are lots of things I’d happily do for free, but most of them wouldn’t plausibly count as work.

+++

Starting to think about vocations from what we desire seems problematic. After all, some of us might want to do things that cannot plausibly be considered a Christian vocation: we might want to be assassins or jewel thieves or hedge fund managers. It is however, one way to express the idea that to discern your vocation is to discern what it means for you to be a Christian: you as an individual, with your particular talents and interests, with your particular social and cultural identities, embedded in your particular contexts. I want to quickly downplay and qualify the “individual” bit of that definition, not because it’s not true, but because people in the West do not need more encouragement to think individualistically. It is important to remember that our social and cultural histories and contexts matter. The Church makes it easy for people who look like me—an ethnically Chinese Malaysian citizen—to realise that such things matter, because we get put on committees for ethnic minority concerns. But not everyone is so lucky, if that’s the word: on the sociological truism that White people “don’t have race”, men “don’t have gender” and straight people “don’t have sexual orientation”, the majority of ordinands are not encouraged or equipped to think about how their social and cultural contexts might fruitfully interact with their sense of vocation. This is a form of prejudice in which everyone loses. It is worth pushing back against. Priests should think about what it means for their priesthood that they are working class or landed gentry, straight or gay, from the Home Counties of the far North. And so should the laity when they consider their vocations think about what it means for them to be a Christian, given their backgrounds. After all, our backgrounds and identities can and should shape our expression of Christian life, and will likely suggest to us something about our ministerial and missional foci, whether lay or ordained.

If it is problematic to begin with what one desires, the opposite move is perhaps even more so. There is an influential strand of thought—for which we can probably blame Kant—that suggests that our vocations have to be the last things we want to do, and about which we would be miserable. If we enjoy it, it must be sinful. I appreciate the sentiment: it resists the temptation we all suffer, toward comfort and convenience. It’s true, of course, that the Christian life is not promised to be easy; but it’s also not promised to be overwhelmingly terrible. Some of us would hate to be a parish priest, and would also be terrible at it. This is not a clue that we should sign up to be the team rector of a large rural benefice. As all good Catholics recognise, grace does not work against nature, but fulfils it.

+++

I have already said something about wanting to de-emphasise individualism. And I’ve also said something about how things like family are also all parts of our vocations, which of course includes vocations to celibacy. Putting these two concerns together, I think it’s important to remember that, odd as it may seem, our vocation is not just about us. That is, we are not the only participants in our own vocations. One of the good things about the discernment process for ordained ministry in the Church of England is that it’s a very social affair. You talk to your parish priest, who puts you in touch with a vocations advisor, who sends you to the Director of Ordinands, who presents you to the Bishops Advisory Panel, who send you to a seminary, who inform the archdeacon of your formation, who presents you to the bishop, who ordains you. You don’t get to be a priest just because you’ve decided that it’s right for you. This is because you are a priest for others: for the Church and for the world. It is also because you are a priest with others: even if you are sceptical about the apostolic succession, you cannot really be an Anglican without acknowledging the collegiality of the ordained ministry. We are not congregationalists.

This sharedness of vocation is no less for Christian vocations more generally than for vocations to ordained ministry in particular. Vocation is not personal ambition. This is countercultural: as a culture, we enjoy stories about individual heroes who reject received wisdom and social objection. Those among us who consider ourselves progressive or liberal might well fall for this trap more than others, thinking that the only way to make things better is to reject the stuffy consensus and authoritarian hierarchy. And sometimes, of course, that’s right. And there’s even an element of that in biblical stories, including the gospels. But it’s all too easy to take this too far. The idea that we know best to the exclusion of anyone else is both ignorant of the psychology of introspective myopia and arrogant to the point of hubris. Your discernment of your vocation, in whatever domain, should as a general rule be a social act.

No where is this clearer than in the case of married persons discerning their vocation. It should be obvious that the discernment of a vocation—lay or ordained, secular or religious—has to involve one’s spouse, not least because the sharing of vocations is a proper part of the broader sharing of life that constitutes marriage. This is not to say that both members of the married couple are equally called to a thing whenever one member is: ordination to the priesthood is not a buy-one-get-one-free-deal. However, married couples’ vocations ought not contradict one another’s, in much the same way that individuals’ vocations—or rather, the various aspects of our lives that together are described as our vocation—ought not be in irresolvable conflict. What is true about married couples is true more generally about the other individuals and groups that count as “stakeholders” in our lives, though perhaps lesser in degree.

+++

To summarise, five points:

- Vocation is work one would do for free if one could.

- Christian vocation is the particular Christian life one is called to live.

- Christian vocation is commensurate with one’s talents and interests, but also one’s backgrounds and identities.

- Christian vocation is for the Church and world, and with others.

- Christian vocation is discerned in community, not alone.

To these, I want to add two observations in closing. The first is that we must be open to the possibility that some jobs are just not appropriate expressions of Christian vocation. We seem to have lost our backbones about this, except in very exceptional cases. Long gone are the days when the Church would forbid Christians from being soldiers, for example. Now, this is not to say that we should bring back those days exactly: there may be differences in what being a soldier entailed back then compared to now that made this occupation unsuitable for a Christian. But the general idea that some mainstream jobs are, in their current incarnation, poor loci for the expression of Christian life is one that we ought to revive.

The second observation is related, which is that it is worth attending to what we, as a society, have implied are vocations in something like the Christian sense, and not just jobs. I have already mentioned artists, musicians, and schoolteachers, and their common attitude toward the relationship between work and remuneration. There is another side to this, which is that we have—albeit less and less so in recent years—been happy, as a society, to support certain kinds of work, including the fine arts, teaching, and medicine. We do so by funding the training required for this work, and by offering bursaries and grants. There are, as far as I know, no public funds made available for someone to train to be a hedge fund manager. To attend to what we, as a society, have decided counts as work that serves the public good is not, of course, to pretend that representative democracy infallibly discerns vocations. It does, however, mean that the idea that not all work is created equal is already recognised at least implicitly in our practices as a society.

A print-friendly version of this post is available here.